Christos Chatzifountas <christos.chatzifountas@yahoo.gr>

Differential privacy AKA how to protect individuals

Synthetic Database

Our main purpose is to be able to draw information from a database of genomes (Haplotypes) and at the same time, to protect individuals from exposure. In essence we want to expose a subset of the database that can give a lot of information, and no particular individual is identified as overly important. This subset is called a [red]#Synthetic [red]#Database.

Introducing utility and noise

Differential privacy [DP] builds conceptually on a method known as randomized response. The key idea of that methods, is that when introducing mechanisms that add noise to the output of a query, private information is hidden (because is noisy, "corrupted") but more general information, like mean values and standard deviation is preserved

Randomized response was a common technique applied to surveys [biz] and is prior to Differential privacy. The later is more involved and suited to modern complex databases with more sophisticated mathematics involved. The reader can consult [DP] a copy of which that can be found here But for the purposes of this blog we will at the very least need the following defintions

Let \(X\) and \(X'\) be two databases that differ only in one element (row/record). We call these databases neighbors. A selection algorithm or query \(\mathcal{M}\) with set of all possible output values \(S\) is said to be Differentialy Private if and only if for any \(s \in S\)

Nowadays we know a lot of mechanisms that are Differentialy private, the most common ones are the Randomized response , the Laplace and the exponential mechanism. From these three only the exponential mechanism is important to us, because it allows to select elements when it is impossible to directly add noise to the output of a query, as is for example for queries with no numerical output

Let \(D\) be a set of database, that we want to extract information from and in a private manner, and \(\mathcal{R}\) be the set of outputs to a query (that might not be numerical in nature). Assume that we have \(u:D \times \mathcal{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) a "scoring mechanism" that we refer as the "utility function". One can think the utility function as a way to assing an score to query output and measure its significance, whatever the query might return.

If \(\Delta u\) is the maximum absolute difference that any two neigboor database can have then

The exponential mechanism is just to select an \(r\in \mathcal{R}\) with probability proportional to \(e^(\frac{\epsilon u(x,r)} {2\Delta u})\)

The quantity \(\Delta u\) is super important. The intuition behind is that we do not want to select an element very far from the scope of the query and \(\Delta u\) puts that restriction in place

That will be enough to digest for now. There is also one last tool, the composition theorem, that we will not introduce formally. It suffice to say that when one makes differentially private queries in succession, the result also preserves privacy.

The reader should at least keep in mind two things: We need to add noise to Haplotype selection. The way to do that is via the exponential mechanism.

Defining utility for Haplotypes

A Haplotype is collection of "words" like GCAG GGCTAG etc etc. We want to select words and make them available for statistical analysis, without making available information with respect to a particular word. The first thing to avoid is picking rare individuals, because theese are almost surely uniquely identified in the haplotype. We also know that nick individuals are very dense, almost all words in a haplotype is unique.

In essense we need to 1.) Select individual words that appear more than once 2.) Don’t expose the information of how frequent is a word We expect that very frequent individuals are not many. We will keep it simply and create a utility function based only the frequency of the words in a Haplotype.

Let \(\mathcal{R}\) be the non negative integers. If \( H \) is the set of all words in a Haplotype then \(\phi: H \rightarrow \mathcal{R} \) is the function that represents the number of appearances of a word in that haplotype. We define the utility function \(u(s,r): H \times \mathcal{R} \rightarrow [0, +\infty) \) as follows: \(u(s,r) = r\) iff \(\phi(s) = r \) and \(u(s,r) = 0\) otherwise

There are other variations of utility functions we could choose. For example instead of \(\phi(r)\) we could have similar behaviour with \(\log (\phi(r) )\), or we could take into account and incorporate the size of the word and get a little better selection of long words, but having \(\phi(r)\) is a bit more convenient since \(\Delta[u\) = 1] since if neighbors databases (collection of words) differ in one word, the different in frequency is either 0 or 1.

Now we can proceed with the database sampling algorithm

The algorithm

Now that we have the utility function we will apply the principles of Exponential mechanism. That is, we will swear the queries, in essence with approximating sampling from \(Pr(s) = e^{\tfrac{\phi (r) }{2}} \) The sampling process will be iterative and the end result would be a set of words that constitute a synthetic database.

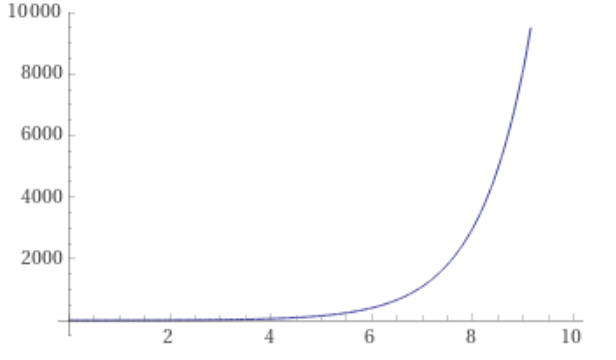

Observe that the sampling function

depicted below has a very very steep curve

That means, that sampling from it will give as haplotypes very close to the ones with the maximum frequency, most of the time. Previously we created a very involved wrapper around BGWTGRAPH -using SWIG- which is the de facto tool for manipulating Haplotypes.

Thanks to SWIG we have used the SearchState struct methods size find and extend to implement the following function to racket

(define (sample-single-state graph #:epsilon [ε 0.1] state)

(define state-list (map (λ (x) (convert-void x)) (GRAPH-extend-to-valid-states graph state)))

(define max-frequency (SearchState-size (find-max-frequency state-list)))

(define Δu (log (/ max-frequency (+ 1 max-frequency))))

(define utility (make-utility ε Δu))

(map (λ (x) (utility (SearchState-size x))) state-list)

(define calculated-utilities )

(convert-void (car (sample-distribution calculated-utilities state-list 1))))Here (sample-distribution) is a custom C++ function that allows us

to sample from a function, when the range of the function can be explicitly calculated.

We call the sample-single-state recursively - eachtime we feed the output of the previous time.

Each time we extend a word to a bigger word with possible, maximal frequency maximal utility

until the resulting word has no extensions. That way we obtain a haplotype that has a high probability to be as large as possible

You can build and see the whole process here

The virtue of that method is that each time we extend a word we don’t give away weather the word is that useful to us, and the same is true for the end result due to the composition theorem. We might loose information on the individual that way but by repeating that process a reasonable number of times we get a collection of words that have a good mean utility, since statistical information is not sewed by randomness. This kind of collection is a good candidate for a [red]#Synthetic [red]#Database.

Challenges and Next step

Our main purpose is to build tools so that individuals can share genomic data safely. While the mathematical challenges are almost solved, making GBWT and GBWGRAPH - which are projects indented to manipulate genomic data - available outside a C++ project has been proven a Herculian task as demonstrated in my previous post, and the wrapper created with swig is unlikely to sufficiently improve usability. Another much more promising tool is [odgi] It is very mature and recently has exposed a friendly C foreign function interface - ipso facto - it worths investigating